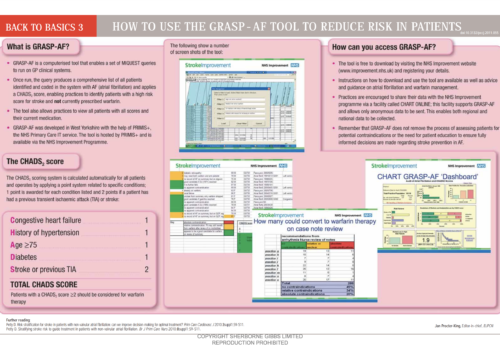

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the commonest cardiac arrhythmia seen in primary care and, if left untreated, is a significant risk factor for stroke. New guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) include some practice-changing recommendations on diagnosing AF, the role of aspirin and the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), and shared decision-making to ensure patient-centred care.