Recognition of the diverse areas of the brain and multiple neurochemicals and hormones involved in regulation of appetite, satiety and metabolism helps to explain why obesity treatment needs to be individualised and is more complicated that merely instructing people who are living with obesity to eat less and move more. On the contrary, it requires strategies to address the psychological, behavioural and physiological processes that contribute to weight gain and which impede efforts to sustain weight loss after it has been achieved.

Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30kg/m(2). It is subclassified into class I (BMI ³30 to <35), class II (BMI ³35 to <40) and class III (BMI ³40).(1) The pathogenesis is heterogeneous, complex, and multifactorial, involving an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure with subsequent disruption of metabolic homeostasis.

Studies have demonstrated more than 140 genetic chromosomal regions, particularly in the central nervous system, that may contribute to a genetic predisposition for obesity. Only a few genes with large effect size have been identified, and they might be responsible for specific syndromes with obesity as a core symptom. However, in general, obesity is thought to be associated with a large number of genes with small effect size.(4)

Appetite control

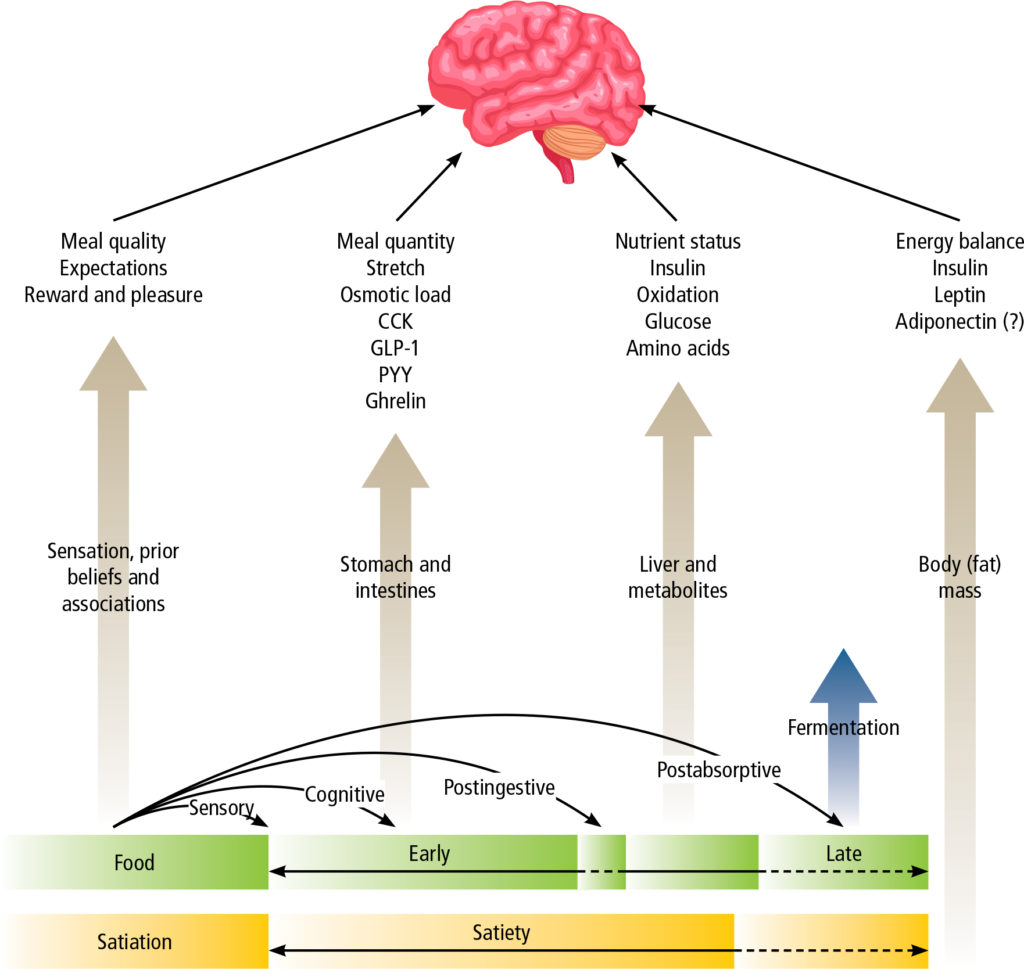

Appetite and satiety are influenced by sensory, cognitive (thoughts and expectations) and emotional factors, meal quality (macronutrient composition, energy density, physical structure and sensory qualities) and quantity, nutrient status and energy balance (Figure 1).(5) The motivation to eat may be related to hunger (homeostatic eating) or pleasure (hedonic eating), and normal eating behaviour (stimulation or suppression of appetite) is tightly regulated by interaction between gut hormones, leptin signalling from adipose tissue, hypothalamic nuclei, the dopaminergic reward system and prefrontal inhibitory influences.(4,6,7)

The basomedial hypothalamus is the principle centre that regulates satiety and hunger. It is influenced by peripheral signals from circulating metabolites and hormones, and neural signals from the gut conveyed by the vagus nerve and brainstem (Table 1). The integrative capacity of the hypothalamus is also greatly influenced by communication with a number of subcortical (limbic) and cortical areas of the brain responsible for reward and learning, monitoring of nutrient status, salience, motivation, desire and craving, autonomic control and satiation, executive function and decision-making. Imaging studies show that several brain areas and networks are differently affected under conditions of fasting, weight loss (induced by both calorie restriction and bariatric surgery), refeeding, overfeeding, exercise, hormone infusion, leanness and obesity, as well as voluntary cognitive control. In obesity, this normally well-coordinated brain system is dysregulated so as to promote weight gain (e.g., increased appetitive/anticipatory and consummatory responses) and resist weight loss (e.g., absence of satiation after a meal). In addition, in some (but perhaps not all) obese subjects, executive control of eating may be impaired, leading to behaviours comparable to those observed with recreational drug addiction, where food intake becomes both impulsive and compulsive, with a drive to eat in the absence of normal homeostatic and hedonic cues. Conversely, inhibitory networks in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which enable cognitive self-control, are activated to a greater extent in patients with the highest weight loss after bariatric surgery.(4,6,8)

| Table 1. Hypothalamic regulation of appetite | ||

| Peripheral signals | Brain area | Effect |

| Adiposity signals: leptin, insulin | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus: Stimulation of POMC/CART neurons; inhibition of AGRP/NPY neurons | Reduced appetite and reduced food intake |

| Satiety signals: PYY, PP, GLP-1, OXM | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus: Inhibition of AGRP/NPY neurons | |

| Hunger signals: ghrelin | Arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus: Stimulation of AGRP/NPY neurons; inhibition of POMC/CART neurons | Increased appetite |

| Vagal afferents | Nucleus tractus solitaris | Feeding Gastric emptying Metabolic rate |

| Satiety peptides: GLP-1, amylin | Area postrema | |

Caloric restriction, which initially in the short-term may facilitate weight loss, but is associated with acute compensatory changes which promote weight gain

Why do patients regain weight after successful weight loss?

Caloric restriction, which initially in the short-term may facilitate weight loss, is associated with acute compensatory changes, all of which promote weight gain. These include a substantial and disproportionate reduction in energy expenditure, reduced levels of leptin, amylin, peptide YY (PYY) and cholecystokinin, and increases in ghrelin and subjective appetite, and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP). Studies show that these changes persist for many years, even after the onset of weight regain.(9-12) Consequently, successful attempts at weight loss are thwarted and it is very difficult for the person with obesity to maintain their new weight in the long-term.

Once obesity has been established, adipose tissue releases adipokines, which directly contribute to systemic inflammation, immune dysregulation, insulin resistance, hyperglycaemia, and endothelial dysfunction. Lipotoxicity resulting from lipolysis and increased free fatty acids, as well as production of proinflammatory cytokines by a dysregulated immune system and mitochondrial dysfunction further contribute to systemic inflammation, a proatherogenic state and other characteristic features of the metabolic syndrome, including hypertension and dyslipidaemia.(4,13) Consequently overweight and obesity are associated with significantly increased risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hepatic steatosis and a multitude of other adverse health conditions.

The role of the gut microbiome in obesity

There is emerging evidence that the gut microbiome, and especially gut bacteria, play an important role in the development of chronic diseases, including metabolic diseases and obesity. Dietary and environmental factors profoundly affect the composition of gut microorganisms, which mediate systemic effects through fermentation of dietary fibre to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) that are physiologically active. A healthy diet, high in nutrient to calorie ratio and complex carbohydrates, and high in fibre, promotes gut microbiome diversity. The opposite is true of unhealthy diets with low nutrient to calorie ratio, low in fibre, and high in refined carbohydrates, sugar, and fat. A healthy microbiome promotes gastrointestinal mucus production and an intact gut barrier.

Gut microbiota influence brain function through interaction between microbial products (e.g., SCFA) and specialised cells in the gut, such as enteroendocrine and enterochromaffin cells, which communicate with the brain via the blood stream or vagus nerve, and also by interacting with gut-based immune cells. Conversely, the brain also modulates the gut via the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for regulating gastrointestinal processes such as immune activation, intestinal permeability, gut microbial abundances, and microbial gene expression patterns. This bidirectional brain-gut-microbiome (BGM) signalling allows for extensive communication and regulation that ensures adaptation to dietary patterns and to different emotional and environmental states. Consumption of an unhealthy diet and persistent psychosocial stress lead to reduction in the quality and diversity of the gut microbiota, associated with reduced abundance of several microbial taxa that have been shown to help maintain gut health and reduce the risk of obesity and other metabolic diseases. This is associated with, among other effects, reduced integrity of the gut barrier, increased intestinal permeability and systemic immune activation, which affects many organs in the body, including the development of neuroinflammation in the brain. Ultimately this leads to dysregulation of the BGM, abnormal feedback mechanisms and disruption of normal eating behaviour.(7,14-16)

Stigma and discrimination

By the time they seek medical assistance, most people with obesity have tried multiple attempts at dieting. However, due to the metabolic compensatory changes that occur with weight loss, dieting, while frequently effective in the short-term, does not lead to long-term changes in weight. It might even be counterproductive. Regardless of the type of diet, over time, the vast majority of dieters regain the weight they lost and around one-third to two-thirds (or more) actually regain more weight than they lost during dieting.(17) Therefore, even with a concerted effort to implement lifestyle changes, weight loss and maintenance of a lower weight are very difficult.

The difficulties associated with achieving sustained weight loss are poorly understood, both by society in general and by overweight people themselves. Consequently, overweight people are often subject to bias and shaming, being unfairly regarded as lazy or gluttonous. Manifestations of this may be subtle or overt, ranging from generalised negative weight-related attitudes, biased beliefs and assumptions relating to obesity (i.e., judging a person’s values, skills, abilities or personality based on their body weight or shape); stigmatisation with social stereotypes; and overt discrimination resulting in unjust treatment because of body weight.

Experiences of stigma and discrimination often begin in childhood and are pervasive in all areas of life (Table 2).(18) Weight stigma in healthcare is particularly pernicious. Almost two-thirds of patients with higher BMI reported experiencing stigma from a doctor, nurse, or dietician. Complaints included that doctors spent less time with them, provided less health education than they did with lower BMI patients, and attributed symptoms to weight without a proper assessment, resulting in missed diagnoses. Patients were counselled to ‘work harder at diet and exercise’, assigned an unachievable ‘ideal’ target weight, but were also denied access to a medical intervention (pharmacotherapy and surgery) until they could show they ‘can commit to weight loss behaviour’.

| Table 2. Sources and consequences of weight stigma | |

| At school | Bullying from peers; teachers have lower expectations. |

| In the family | Stigma; negative emotional consequences; shame leading to eating disorders; parental shame with emotional and behavioural consequences. |

| Workplace and society | Verbal and emotional discrimination: teased, insulted, made fun of, or rejected by friends, family, or colleagues. |

| Barriers in day-to-day life | Undersized chairs in public locations, transport, or lack of appropriate sized equipment in medical clinics (e.g., BP cuffs, weight scales). |

| Policy | Denial of access to proper supports when treatments for obesity are not available; evaluation of lifestyle policy and programs in terms of population weight, so that success is measured on population weight loss, whereas weight loss is not necessary to improve quality of life. |

| Media stereotypes | Overweight people are aggressive, comical, unpopular, lazy, unintelligent, and faceless. |

| Advertising and social media | Portrayal of what is an ideal or desirable/attractive physique; sensationalised and false advertisements for weight loss products; claims that what has helped one person with weight loss will work for all; social media algorithms targeting ‘plus-sized’ influencers. Consequences are low-self-esteem, feelings of failure or inferiority, and avoidance of healthy behaviours, because they have not matched up to the expectations portrayed by media. |

Consequences of weight stigma are significant and far-reaching.

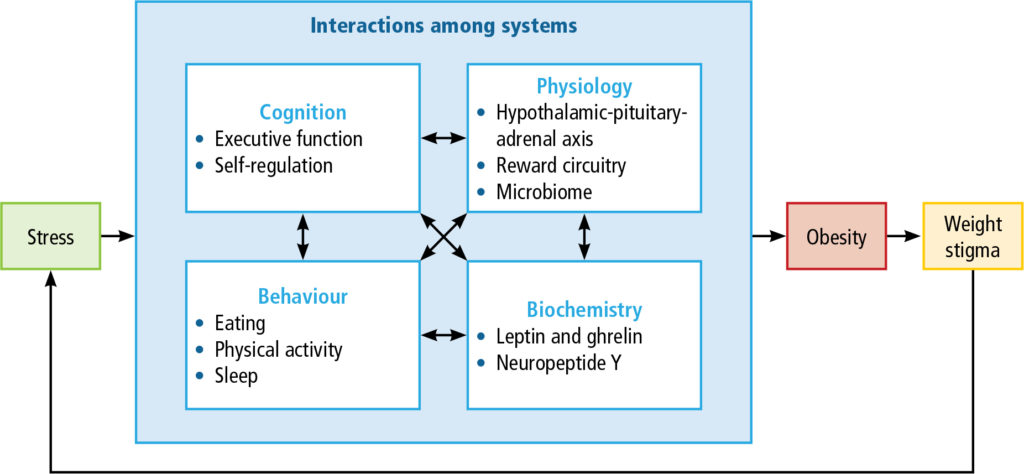

They include emotional disorders such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, self-dissatisfaction, feelings of failure and inferiority; eating disorders; and avoidance of places, people, and activities. Patients may internalise bias, believing they deserve the negative weight-biased beliefs, resulting in unhelpful narratives (e.g., I’m lazy; my weight is my fault; I can’t lose weight so what’s the point in trying) that interfere with seeking healthcare or persevering with weight loss interventions. Weight stigma is stressful and, through a complex positive feedback loop, is believed to directly contribute to maintenance of obesity and further weight gain (Figure 2).(18)

For these reasons, awareness of weight stigma and proactively addressing it are essential to provide effective weight management interventions (Table 3).

| Table 3. Considerations to reduce weight stigma |

|

Approaches to management of obesity

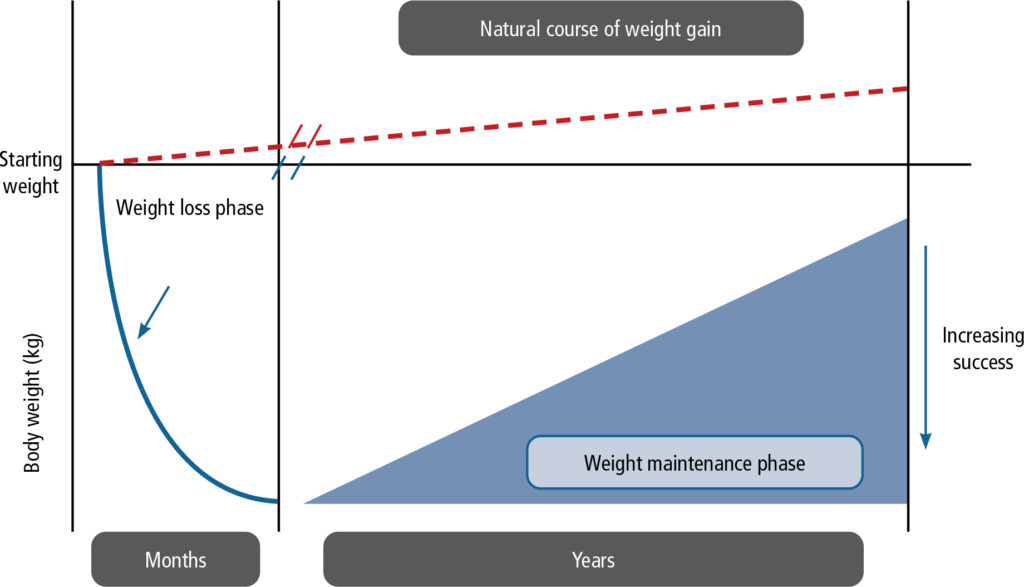

Successful weight management is a lifelong effort, with an initial phase of weight loss followed by continued attention to lifestyle modification and, where necessary, ongoing treatment to maintain body weight and prevent excessive weight gain (Figure 3).

Even modest weight loss significantly improves obesity-related complications and quality of life.

Indeed, 5% to 10% weight loss is associated with significant reductions in type 2 diabetes, dydlipidaemia, blood pressure, obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.(1,4) However, despite the increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide, it remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Studies indicate that pharmacotherapy for obesity is prescribed for fewer than 2% of patients who would qualify for it based on the current recommendations (BMI ³27 with obesity-related comorbidities or BMI ³30kg/m(2)). This trend is true across the spectrum of BMI. In a study of prescribing trends among almost 30 000 people with BMI ³27kg/m(2), only 3.4% of those in the most severe category (³40kg/m(2) received a prescription for anti-obesity medication.(19) Reasons for undertreatment are multiple (e.g., lack of awareness among patients and clinicians; few weight management specialists; limited treatment options and reimbursement; weight-based discrimination). Even when it is treated, there is a considerable delay of many years between reaching a critical weight that would benefit from treatment and actually receiving treatment.

Making a stepwise plan with the patient

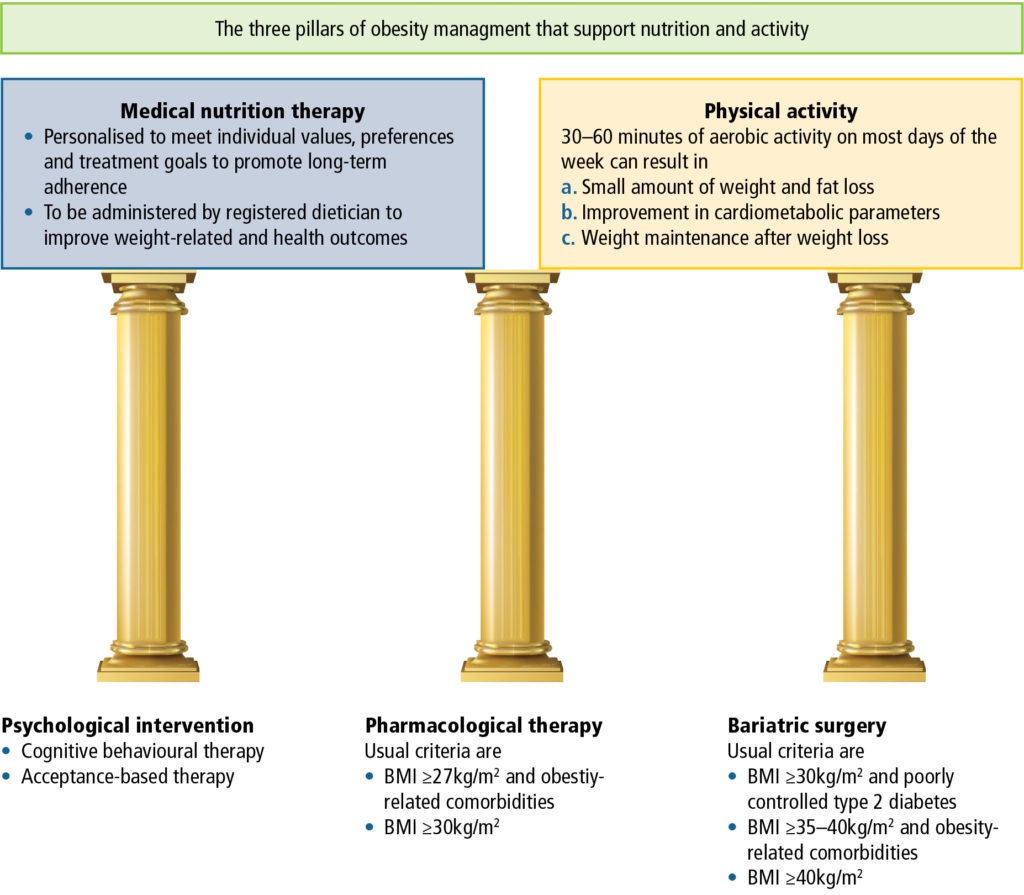

Obesity has a complex and variable aetiology. Furthermore, as already described, weight loss attempts are accompanied by compensatory changes in metabolic rate, gastric hormones and neurochemical pathways that occur with, and persist after, weight loss, making weight maintenance extremely difficult. Consequently, for the majority of people with obesity, lifestyle management alone is not sufficient for long-term weight management. With diet alone, 70% of patients regain weight within one year, and 85% to 90% regain their weight in two years. When diet is combined with behaviour modification, 70% regain weight by 30 months and weight is back to baseline levels within five years. After inclusion of exercise, only approximately 42% will maintain weight loss at two years. Therefore, it is clear that a step-wise approach to weight loss is not helpful for most patients. Effective treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach and combination treatment to address the root causes of obesity (Table 4), while working with the patient to understand their context and culture to develop a personalised treatment plan (Figure 4).

| Table 4. Root causes of obesity for consideration in personalising a treatment plan(1) |

|

Important members of the multidisciplinary team might include, among others, a general practitioner, physician, endocrinologist, cardiologist, gastroenterologist, psychiatrist, psychologist, pulmonologist, surgeon, nurses, nutritionist, and specialists in sleep medicine.

Patients are heterogeneous in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, genetics, comorbidities, concomitant medications, weight, body fat distributions, socioeconomic status, culture, personal preferences and other factors. There is also considerable variation in response to weight loss medication in terms of efficacy, susceptibility to adverse effects and the additional health benefits associated with some of these treatments.

One treatment approach does not suit all and management should be individualised.

Studies indicate that patients who achieve an early response on therapy are more likely to achieve the best outcome. This can be facilitated by early diagnosis and intervention in primary care; patient education; early utilisation of pharmacotherapy; frequent follow-up (either face to face or virtually); availability of specialised centres for referral when necessary; and efficient communication between members of the healthcare team. As is true for other chronic diseases, long-term follow-up should be the standard of care.

A typical approach to assessment and treatment of a patient with obesity consists of each the following steps:

| 1. | Assess readiness Patients who are not ready for change receive disease education and are reassessed at the next visit. |

| 2. | Screen for complications Important comorbidities include prediabetes and diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obstructive sleep apnoea, polycystic ovary syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and depression. |

| 3. | Management of microenvironment A comprehensive program of lifestyle modification is the cornerstone of weight management. This includes attention to diet and nutrition (type and timing of meals), physical activity, stress, sleep, and current use of weight-promoting treatments. |

| 4. | Set goals Patients should aim to achieve at least 3-5% body weight reduction over three months, with improvement in comorbid conditions. Additional measures of improvement include quality of life scales and Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS), which evaluates obesity-related risk factors, physical and psychological symptoms, and functional limitations. |

| 5. | Combination therapy Active treatment includes psychological assessment, obesity education, behavioural treatment and anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Endoscopic treatments and weight loss surgery will be considered, depending on the patient’s response to pharmacotherapy and BMI. |

| 6. | Continued follow-up and weight assessment With use of telemedicine for continued monitoring. |

The role of lifestyle modification

Healthy dietary choices and physical activity are the cornerstone of health and wellbeing. All weight loss programs begin with attention to diet and exercise, and both are required for weight loss and maintenance of weight loss.

Healthy nutrition and calorie restriction

Any diet that restricts calories can result in weight loss, and there is no evidence that any specific diet is more effective than any other in that regard. However, a diet must also be nutritionally sound, assisting patients to consume more healthy foods and restrict consumption of unhealthy foods (Table 5). Because many people eat for pleasure, to reward themselves and to make themselves feel better (hedonic eating), it is important to combine dietary change with behaviour therapy to modify how the patient thinks and feels about food. In this respect, because of past experiences and the negative connotations associated with dieting, and to cultivate sustainable lifestyle change, patients may be more receptive to conversation about ‘nutrition therapy’ or ‘healthy nutrition’ rather than ‘diet’.

| Table 5. Medical nutrition therapy: characteristics of an ideal diet |

|

Usually a low-calorie diet provides 1 000-1 200kcal/day for women or 1 200-1 600kcal/day for men, and for women who weigh more than 80kg or who exercise regularly. Calories may be further restricted for patients who do not achieve the desired weight loss (0.5-1 kg/week), or increased for patients who feel hungry (extra 100-200kcal/day). Certain very overweight patients and those with comorbidities may benefit from a very low-calorie diet (<800kcal/day), which increases the speed and magnitude of weight loss. These diets should only be used in exceptional circumstances, only under strict medical supervision, and adjusted according to weight loss results. Some practical dietary advice for all patients is listed in Table 6.

| Table 6. Practical advice for maintaining a healthy diet |

|

Physical activity

Physical activity is an integral part of obesity management. Combining physical activity with diet increases weight loss, and maintenance of a regular exercise programme can help sustain a healthier body weight once weight loss has been achieved. Indeed, continued exercise is the most important predictor of maintained weight loss. An ideal programme may comprise endurance, resistance, and high-intensity interval exercises (and preferably a combination of these), but needs to be tailored to the capabilities and physical limitations of the individual. Current guidelines recommend that all people aim to engage in at least 30 to 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity most days of the week.(1) Furthermore, studies show that the more active a person is (hours per week), the greater the benefit in terms of achieved weight loss. Nevertheless, there are many additional benefits to regular physical activity (Table 7).

Exercise can improve the health consequences of obesity even in the absence of weight loss.

| Table 7. Benefits of physical activity | |

|

|

Role of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Internalised weight bias and wanting are key drivers of obesity. CBT aims to change the patient’s relationship with themself and with food, and thereby change food-related thoughts, decisions, and behaviour. Key components of CBT in obesity management are to address (a) internalised weight bias; (b) learned habitual eating and craving (wanting); and (c) patients’ understanding of obesity as a chronic disease that requires long-term change. It aims to cultivate self-esteem, self-regulation and self-efficacy and provide patients with practical knowledge to manage their weight. Generally, CBT is guided by motivational interviewing techniques, beginning by asking permission to discuss weight (to demonstrate compassion and empathy and build patient-provider trust), listening and summarising (including identification of goals that are meaningful to them), informing about and inviting behaviour change, agreeing on goals, and assisting with drivers and barriers of change (Table 8).

The starting point of effective CBT is to understand how the patient thinks about obesity and uncover internalised weight bias. Internalised bias is associated with greater weight gain, poorer mental and physical quality of life, less self-efficacy with respect to eating and physical activity, greater eating as a coping strategy, more avoidance of going to gym, poorer body image and greater perceived stress (which in its own right is a driver of obesity).(21) Education should be focused around the biological nature of obesity, including genetics (family history, the instinctual drive for food), appetite regulation, neuroendocrine functions that promote weight regain following weight loss, and how the social environment encourages consumerism and plays into the current obesity pandemic (e.g., ultraprocessed, easily available foods rich in fat, salt, sugar; larger portions; advertised to look healthy).(22)

The second key component of CBT is to address craving that leads to impulsive and compulsive eating. The ‘wanting’ component of reward sensitivity is primarily associated with the brain’s motivational mesolimbic dopamine system and is distinct from ‘liking’. It is characterised by associative and reward learning during which exposure to foods of reward value at the same time as internal stimuli (e.g., emotion and internalised weight bias) and external stimuli (e.g., sight or smell of food) changes the brain circuitry that regulates wanting so that the person associates these salient cues (e.g. presence of food, television, cravings, anxiety, boredom) with food consumption and reward. Exposure to these salient conditioned cues elicits dopamine release, generating a powerful compulsion to eat (incentive salience), which in turn leads to excessive calorie intake beyond metabolic needs.(22,23)

Addressing incentive salience/wanting starts with identifying and drawing the patient’s attention to high risk times, places and cues associated with excessive calorie consumption.

- When, e.g., lunch, afternoon, end of day predinner, dinner, desert, between dinner and sleep;

- Where, e.g., home (what room), office, restaurant, social setting;

- Who is around, e.g., alone, with someone else (name them);

- How often.

Through exploration of their own incentive cues, patients learn the destigmatising message that these settings have been paired so often that they are now subject to the neurological reflexive event we call wanting/craving. Adherence to healthy eating goals depends on the ability to self-regulate and adhere to behavioural recommendations for weight loss despite the challenges posed by these biological predispositions and cues that push individuals to engage in unhealthy behaviours (or nonbehaviours) that impede weight control. Acceptance-based therapy (ABT) is a behavioural intervention designed to help patients manage incentive salience. It teaches patients self-regulation skills, such as ability to tolerate uncomfortable internal states (e.g., urges, cravings, and negative emotions) and reduction of pleasure (e.g., choosing to exercise instead of watch TV), behavioural commitment to clearly defined values that increase motivation to persist in difficult weight control behaviours, and metacognitive awareness of decision-making processes. In a 12-month trial, ABT facilitated greater and more sustained weight loss than standard behavioural treatment.(24)

The gut-brain axis is also actively involved in the control of reward-based eating behaviour. Anorexigenic plasma gut hormones (GLP-1 and PYY), plasma bile acids and symptoms of dumping syndrome after gastric surgery have an inhibitory effect on the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways that are activated by incentive salience. Obesity treatments that influence these pathways, including the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide and bariatric surgery/banding, have been shown to improve control of eating and reduce food cravings and energy intake associated with visual and olfactory cues.(24-28)

| Table 8. Example of CBT script to approach weight bias and wanting |

| An invitation to reconsider internalised weight bias and wanting might sound as follows:

Would you consider….

|

Conclusion

In contrast to popular conception, obesity is not merely a matter of increased size or waist circumference due to overeating and sedentary lifestyle. On the contrary, in people who live with obesity, reduction of calorie intake and increase in energy expenditure alone, although they are important components of weight management, rarely lead to significant and sustained weight loss. Factors involved in the pathogenesis of weight gain and inability to sustain weight loss are multiple and complex. Consequently, obesity care should be based on evidence-based principles that address the root causes of weight gain and the physiological and psychological mechanisms that impede weight loss.

AUTHOR: ALEXANDRA ALDRIDGE