What is Multiple sclerosis?

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a progressive neurodegenerative disease which arises when the immune system mistakenly attacks and damages tissue in the central nervous system (CNS). This inflammation can affect different sites of the body at different times, producing a wide range of signs and symptoms.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a progressive neurodegenerative disease which arises when the immune system mistakenly attacks and damages tissue in the central nervous system (CNS). This inflammation can affect different sites of the body at different times, producing a wide range of signs and symptoms.

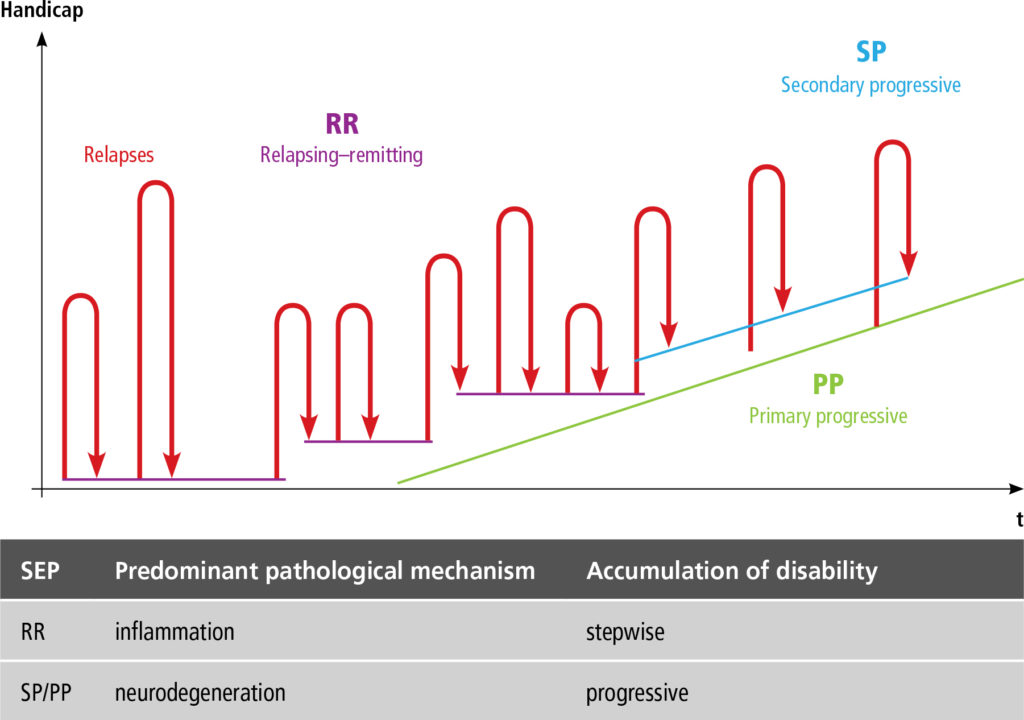

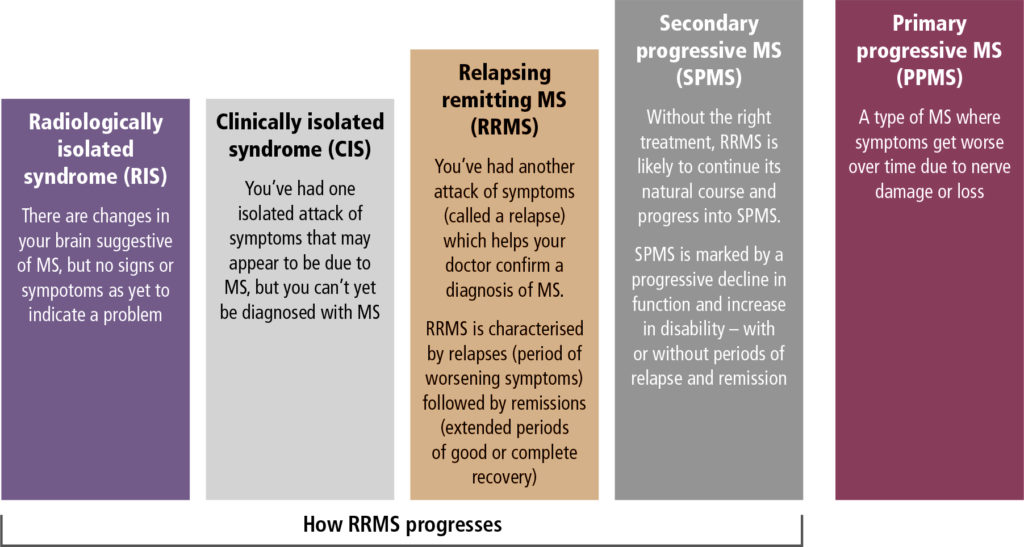

In the early stages of MS there are periods of relapse and remission, with slow disease progression observed over the following decades. From MS diagnoses, 85% are relapsing remitting MS (RRMS) and many of these individuals will eventually develop secondary progressive MS (SPMS). Primary progressive MS (PPMS) represents 12% of diagnoses and the remaining 3% are an unknown MS disease type.

Early and appropriate treatment can markedly reduce disease activity and slow the accumulation of disability, but there is currently no cure for MS. Dr Manesh Pillay shares his insights and experience in the management of the patient with MS, with an emphasis for primary care on the diagnosis and treatment of the early stages of the disease.

What are the risk factors?

Three-quarters of all people with MS are women aged 20-40 years, with a peak at age 29-30 years; males are more likely to have PPMS, with a peak at the age of 40 years. In young adults, MS is the most common acquired CNS disease.(1)

The risk of developing MS is 1-2% if a sibling has MS and in the case of homozygous twins, the risk of both having MS is 30%. However, environmental factors such as low vitamin D intake at a young age, Epstein-Barr virus, smoking and geography (living further away from the equator) seemingly have a greater impact on the risk of developing MS.(1)

What underpins the pathology?

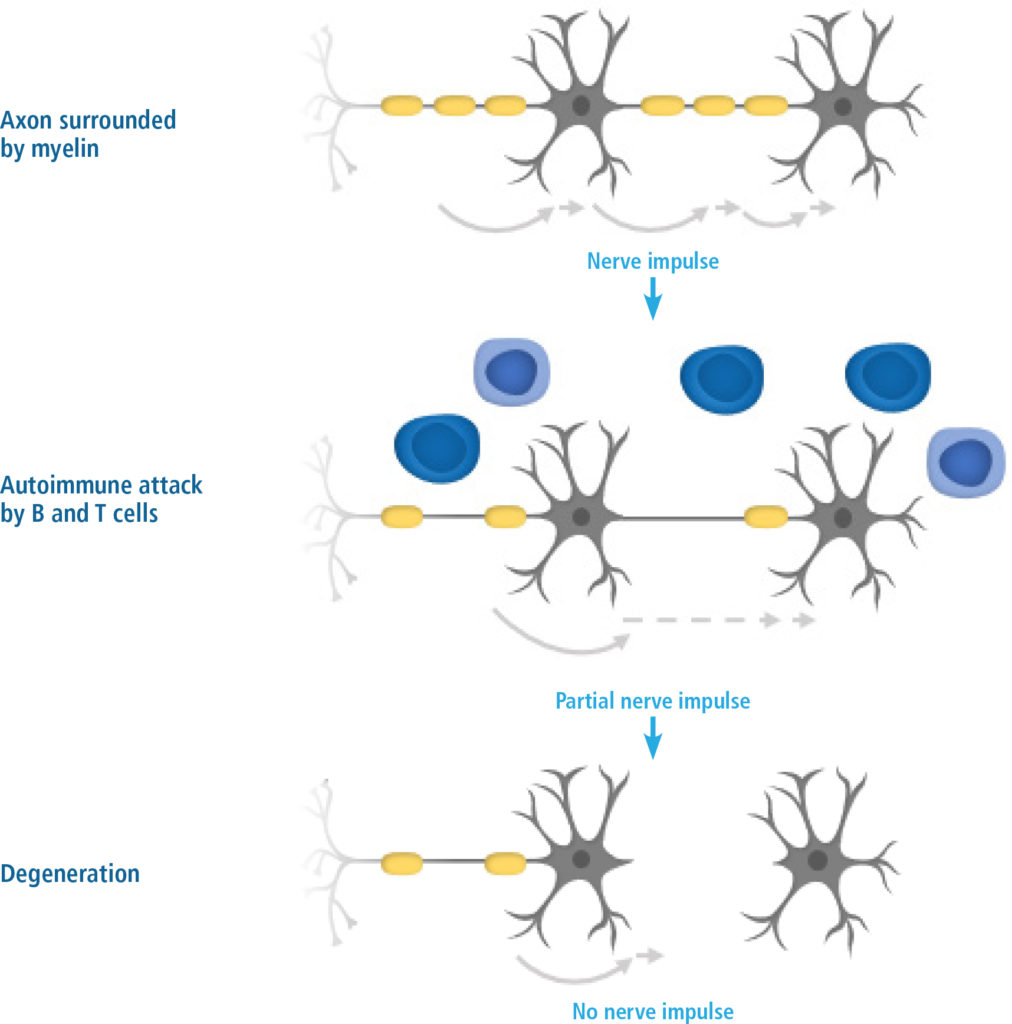

As a chronic autoimmune degenerative disease of the CNS, MS affects the brain and the spinal cord. Damage to the myelin sheath and axons affects signal transduction along nerve fibres (Figure 2), giving rise to the symptoms of MS. Axonal loss due to autoimmune attack by inflammatory cells gives rise to plaque formation early in the disease and is irreversible. Axonal loss progresses to a degenerative phase, which is more difficult to treat because most of the available medications are immunomodulatory.

MS has a heterogeneous clinical course; the disease is highly dynamic, features unpredictable episodes of inflammation and demyelination, and can involve variable, transient, persistent or progressive neurodegeneration.(2,4)

How is the diagnosis made?

The diagnosis of MS is made based on dissemination in time and space; information is gathered from the patient’s medical history, neurological examination, imaging and laboratory testing. The medical history should include an evaluation of symptoms and risk factors for MS and the neurological assessment should encompass sensory, motor and visual symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spinal cord are established tools for the diagnosis of MS, and new developments in imaging technology are enabling MS pathology to be detected with greater sensitivity and specificity. Laboratory testing may be used as an adjunct to verify the diagnosis of MS when other investigations have not provided conclusive evidence; cerebrospinal fluid analysis (IgG and lymphocytes) and evoked potential testing may be useful.(5,6)

The diagnosis of MS is made based on dissemination in time and space; information is gathered from the patient’s medical history, neurological examination, imaging and laboratory testing

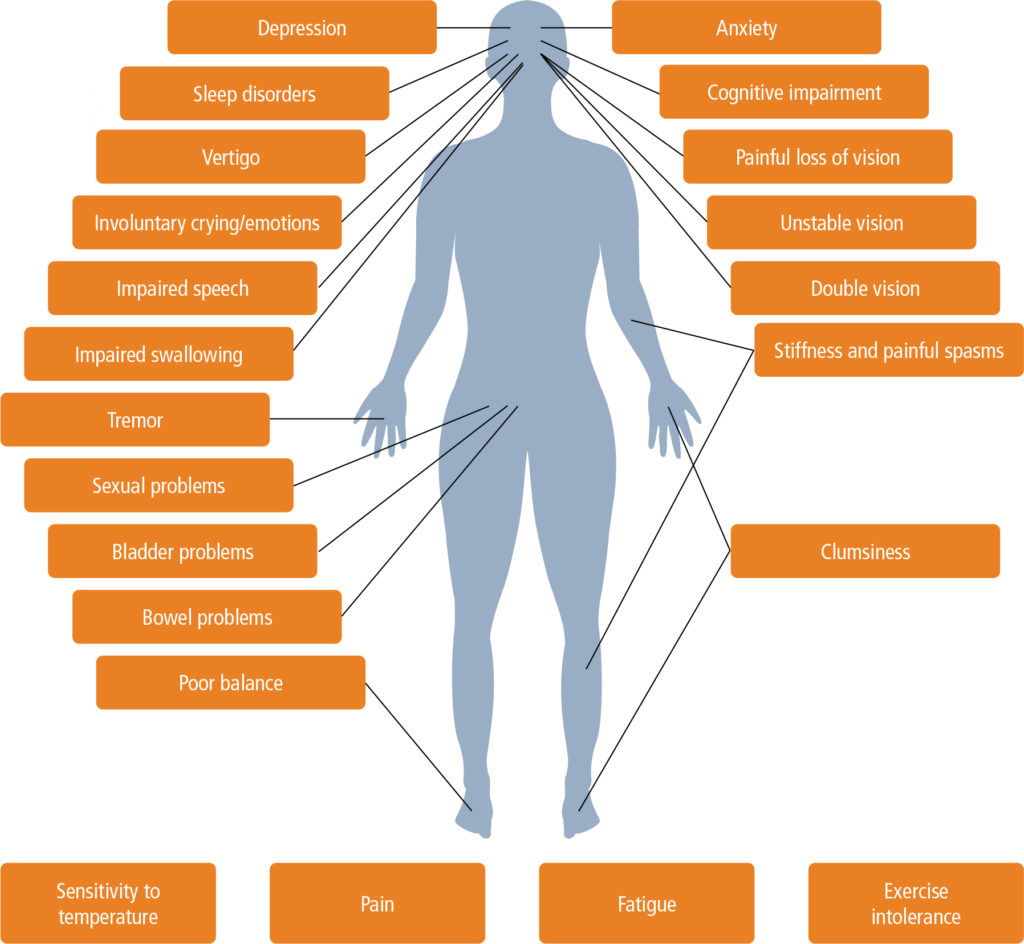

Common symptoms

The symptoms of MS are often non-specific (Table 1); they can be both visible and invisible to others, they are unpredictable, and they vary from person to person and from time to time in the same person. The most common symptoms reported when a patient first visits a healthcare professional are:

- Sensory (40%), including numbness, tingling, burning pain

- Motor (39%), including weakness, stiffness, clumsiness, difficulty with walking

- Visual (30%)

- Fatigue (30%); a feeling of lacking physical or mental energy that interferes with usual or desired activities

| Table 1. Common symptoms of MS |

|---|

|

When to suspect MS

The typical patient presents as a young adult with one or more clinically distinct episodes of CNS dysfunction such as optic neuritis, a brainstem syndrome or a spinal cord syndrome. Presenting symptoms and signs may be either monofocal (consistent with a single lesion) or multifocal (consistent with more than one lesion).

The typical patient presents as a young adult with one or more clinically distinct episodes of CNS dysfunction

Symptoms usually develop over the course of hours to days and then gradually remit over the ensuing weeks to months, although remission may be incomplete. If the symptoms last for more than 28 days, it counts as a second relapse.

A pseudo-relapse is a deterioration in neurological function that is not due to inflammation but that is more likely related to temperature or infection.

| Table 2. Useful questions for ascertaining prior neurological disturbances |

|---|

|

Risk factors associated with progression

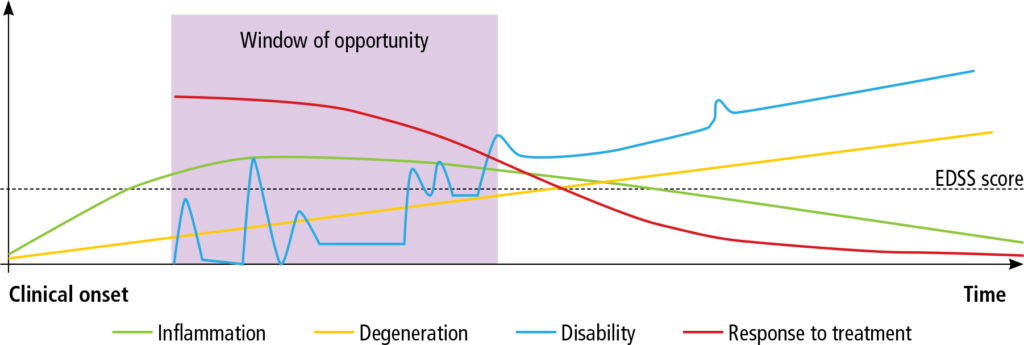

When inflammation is present, the pattern of repeated relapses with complete or partial recovery leads to progression without recovery when neurodegeneration develops (Figure 3). The progression of RRMS is described in Figure 4.

Risk factors associated with progression to SPMS are older age at disease onset, short interval between the first and second relapses, higher and increasing T2 lesion load, and motor deficit with incomplete recovery.

What are the clinical features?

Brainstem nuclei

Optic neuritis and internuclear ophthalmoplegia (impaired induction ipsilaterally, horizontal nystagmus of abducting eye) are the most common presentations in MS. Involvement of the other cranial nerves is not that prevalent, but there can be facial sensory disturbances, loss of taste, auditory problems and vertigo.

Optic neuritis and internuclear ophthalmoplegia are the most common presentations in MS

Optic neuritis has a subacute onset. Patients present with reduced vision, with central and colour loss, and pain on eye movement. Fundoscopy is normal because it is a retrobulbar inflammation. The patient with optic neuritis presents with a Marcus Gunn pupil, where the affected pupil dilates when using a swinging flashlight test. A Snellen contrast chart is useful, as the decreased visual acuity in these patients is more pronounced when moving from a dark to a light background. To have bilateral simultaneous involvement is very rare in MS.

Other impairments

Other impairments that may manifest include bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction, fatigue and cognitive impairment.

Sensory manifestations are a frequent initial feature of MS and are present in almost every patient at some time during the course of disease. The sensory features can reflect spinothalamic, posterior column or dorsal root entry zone lesions, with symptoms commonly described as numbness, tingling, pins and needles, tightness, coldness, itching, or a feeling of swelling of the limbs or trunk. Unilateral or bilateral radicular sensations can be present, and a band-like abdominal sensation may be described.

Sensory manifestations are a frequent initial feature of MS and are present in almost every patient at some time during the course of disease

Corticospinal tract dysfunction occurs commonly in the setting of relapse or progressive disease. Weakness as a result of relapse can involve one or all limbs and, although exceedingly rare, a devastating relapse can result in a permanent inability to walk. More commonly, sustained motor weakness may be partial (residual of a relapse) or worsen gradually as a result of progressive disease. Paraparesis or paraplegia occurs more frequently than significant weakness in the upper extremities; a hemiparesis sparing the face is also common. Most patients with weakness develop spasticity to some degree.

Occasionally, reduced reflexes reflect hypotonia due to cerebellar pathway lesions. Amyotrophy, when observed, most frequently affects the small muscles of the hand; lesions of the motor root exit zones may produce muscle denervation secondary to axon loss.

Be aware of paroxysmal episodes, which are brief, stereotypical attacks of motor or sensory phenomena such as diplopia, focal paraesthesia, trigeminal neuralgia, ataxia, dysarthria and tonic spasms. These features are triggered by a specific movement or stimulus, with no identifiable inciting factor. Paroxysmal episodes are the consequence of a pre-existing lesion.

What are the diagnostic investigations?

Investigations for the diagnosis of MS are listed in Table 3.

MRI remains the most important investigation in the diagnosis and monitoring of MS. Followed over time, MRI scans in MS typically ‘wax and wane’, with the emergence of new lesions and the involution of older lesions. Increasingly, MRI also plays a role in monitoring the effects of treatment and monitoring disease activity.

MRI remains the most important investigation in the diagnosis and monitoring of MS

White matter lesions are best visualised on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences. Active inflammation is best seen on enhanced T1-weighted images. Although the abnormalities found on MRI scans, particularly those seen on a single examination, are not specific for the disease, certain combinations of findings on cerebral MRI have a high specificity for MS; characteristic supratentorial sites include the periventricular region, corpus callosum and juxtacortical areas of the brain, and the presence of infratentorial lesions is typical.

Spinal cord lesions are usually eccentric, dorsal, and span less than two vertebral segments. Spinal lesions may be subtle, and newer sequences such as short time inversion recovery may be more sensitive than conventional T2-weighted sequences.

Recent studies have demonstrated tight correlation between loss of cortical and deep grey matter volume, with cognitive and motor outcomes in MS. Advances in volumetric MRI, resulting in the accurate segmentation of grey and white matter and estimation of volume changes over time, are now being incorporated into multi-national clinical trials.

| Table 3. Investigations for the diagnosis of MS | |

|---|---|

| MRI of the brain and spinal cord | |

| CSF |

|

| Bloods |

|

| Visual evoked potentials, optical coherence tomography | |

Which other disease can mimic MS?

Many diseases can mimic the presenting symptoms of MS (Table 4) and it is important to exclude these when considering the MS diagnosis.(7-9) An alternative diagnosis should be considered if:

- Age <15 or >60 years

- The patient has previously experienced visual, sensory or bladder symptoms

- Clinical course is progressive from onset

- Laboratory findings are atypical

- There are uncommon or rare symptoms

- Symptoms are localised exclusively to the spinal cord or to specific areas of the brain (craniocervical junction, posterior fossa).

| Table 4. Differential diagnosis – diseases that mimic MS | |

|---|---|

|

|

What are the treatments?

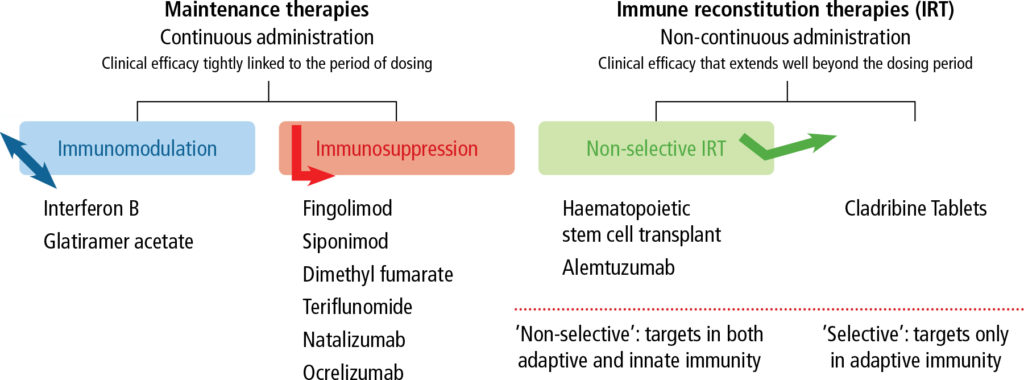

Treatments are available that reduce the disability associated with and the progression of MS. In recent years there has been a significant increase in the types of medicines available, although it has been found that the better the medication at reducing inflammation, the greater the side effects. A proposed classification system for disease-modifying drugs is outlined in Figure 5.(10-15)

How to manage symptoms and comorbidities?

Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration culminate in a variety of persistent symptoms that are not necessarily related to acute relapse. The most common symptoms are spasticity, fatigue, bladder problems, bowel problems, pain, reduction in mobility, and epilepsy and mood disorders. These symptoms are often inter-related, such as pain making spasticity worse and bladder problems worsening fatigue (getting up in the middle of the night to urinate). Be aware of each of these symptoms and that some treatments can be offered; symptomatic treatment is beyond the scope of this review.

Comorbidities in patients with MS are common and are associated with diagnostic delays, disability progression and poor quality of life

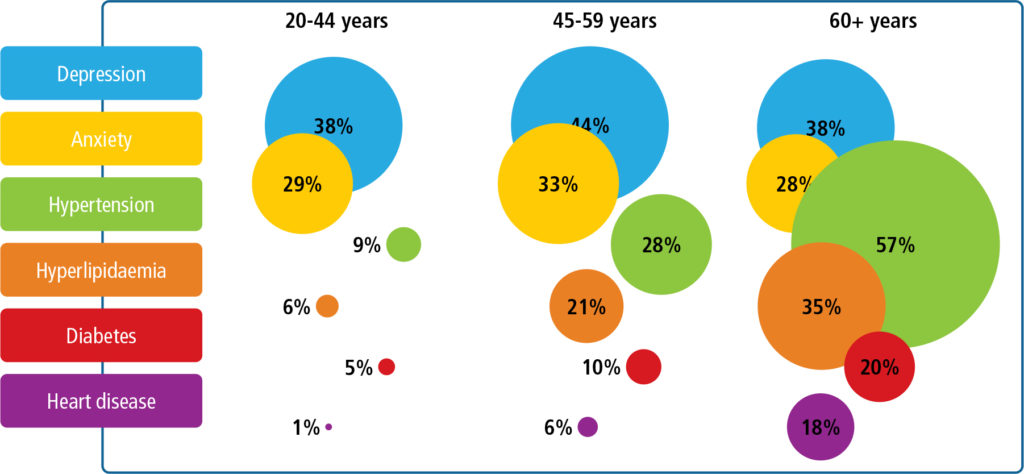

Comorbidities in patients with MS are common and are associated with diagnostic delays, disability progression and poor quality of life. Comorbidities may also affect patients’ treatment choices. Common comorbidities include chronic lung disease, anxiety, diabetes, depression, epilepsy, hypertension and cancer. The incidence of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, obesity and heart disease increase with age (Figure 6).(16-21)

Key stages in the MS care pathway

Consensus standards are structured around the key stages in the MS care pathway, which encompass symptom onset, referral and diagnosis, treatment decisions, brain-healthy lifestyle, monitoring and managing of relapses. Delays often occur between the initial onset of symptoms and the MS diagnosis by a neurologist; contributing factors include delayed patient presentation to a healthcare practitioner, the unavailability of diagnostic tools and a lack of knowledge among referring healthcare professionals, who may miss the signs of MS.

Early treatment is ideal because symptom burden worsens as damage to the brain accumulates (Figure 7); treatment during the early ‘window of opportunity’ may prevent or delay the time to secondary progression. Current immune-directed disease-modifying treatments target the early inflammatory phase of RRMS.

Earlier diagnosis and treatment of MS may preserve brain function, control symptoms, reduce relapses, delay disease progression, improve quality of life and curb costs