The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in England is around 2% of the total population.1 Many of these patients are treated with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to reduce the risk of stroke. To maintain patient safety, clinicians must be educated on how to manage DOACs, from safe prescribing to managing complications. In light of patient-centred care, the NHS states that an anticoagulation service must include “a convenient ‘one-stop’ clinic where patient education, discussion and support, and blood tests, dose changes and follow-up arrangements are all made during the patient consultation”.2

The European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) states that “non-valvular AF (NVAF) refers to AF that occurs in the absence of mechanical prosthetic heart valves and in the absence of moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis (usually of rheumatic origin)”.3 DOACs are often prescribed for patients with AF to reduce the risk of stroke. Due to the rapid onset of action of DOACs, patients do not require a loading dose or bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).4 DOACs have more predictable pharmacokinetics and fewer drug interactions than warfarin so DOAC therapy does not require routine coagulation monitoring.5,6 However, monitoring of AF patients on DOAC therapy includes assessing adherence, risk of thromboembolism, bleeding risk, other side-effects and co-medication as well as blood sampling.3

Stroke vs bleeding risk

NICE guidelines state that the CHA2DS2-VASc score must be used to assess stroke risk in patients with AF.1,7 Consequently, NICE created guidelines for anticoagulant therapy services as well as commissioning guides to aid the implementation of NICE guidance1 following Anticoagulation Europe’s advice.8 In 2016 the Medicines Management Committee and Cardiovascular Clinical Working Group of the Hillingdon Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) ratified and implemented a policy9 with guidelines on the use of DOACs for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in NVAF.

The European Society of Cardiology has designed a protocol for the initiation of anticoagulants in AF patients and monitoring of bleeding risk in these patients.10 HAS-BLED11 is a common risk stratification tool for bleeding; it identifies patients at risk of haemorrhage requiring hospitalisation or resulting in a decrease of 2g/L in haemoglobin or requiring blood transfusion.12 Monitoring allows for potential dose adjustments, revision of anticoagulation indication and appropriate preventive management.

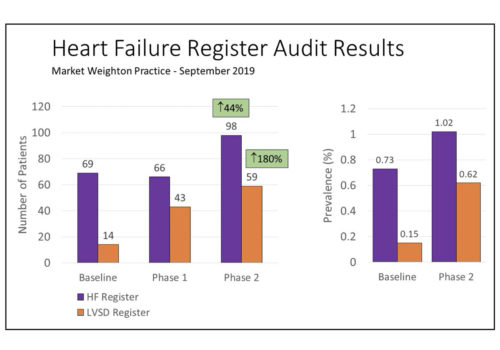

Auditing DOAC monitoring

We conducted an audit to assess the adequacy of monitoring of NVAF patients on DOAC therapy in accordance with the Hillingdon CCG policy. The objective of the audit was to compare performance in clinical practice based on data collected with the policy’s criteria and standards, with a focus on blood sampling requirements and drug dosing for the DOACs rivaroxaban and apixaban.

We performed a standards-based clinical audit retrospectively at a surgery in Northwood, London (Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) in September 2017. We included a total of 103 active patients who received their first GP prescription for apixaban (n=55) or rivaroxaban (n=50) between September 2015 and September 2017. We obtained patient data analysed in this audit from the EMIS Web system. Three variables (Frequency of blood sampling; Dose adjustment; and baseline eGFR [MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease equation]) were investigated and compared between apixaban and rivaroxaban.

Target criteria

Blood sampling involved checking for haemoglobin levels, renal function and liver function. All patients required at least once-yearly blood sampling. For patients >75-80 years, or with electronic frailty index (eFI) >0.3, tests were performed every 6 months. For patients with eGFR ≤60 ml/min, the monthly interval for rechecking was determined by dividing the patient’s eGFR level by 10. For patients with an intercurrent condition that may impact renal or hepatic function, blood sampling must be performed whenever indicated. Patients with eGFR <30ml/min or two of the following: age >80 years, weight ≤60 kg, creatinine > 133mmol must be on a lower dose of apixaban. All patients with renal impairment (eGFR 60 ml/min) should also be on a lower dose of rivaroxaban. The standard is that allpatients should have their baseline eGFR measured, as an indicator of baseline renal function and to allow for initiation of DOAC therapy at the appropriate dose.

Results

Approximately 1 in 7 patients had mild-moderate to severe frailty based on eFI > 0.3. A majority (54%) of patients did not have regular blood sampling as recommended in the guidelines of the CCG policy. Far fewer patients on rivaroxaban had regular blood sampling (18%), compared with 28% of patients on apixaban who had regular blood sampling. Patients who did not have regular blood sampling were often started on treatment a longer time ago. It was found that 11% of patients on apixaban and 12% of patients on rivaroxaban were on excessive doses of therapy for their age and eGFR. Since the CCG policy was implemented, only 50% of patients on apixaban and 30% of patients on rivaroxaban had their baseline eGFR measured before commencing DOAC therapy.

Importance of blood sampling

The most important implication derives from our finding that the majority of patients did not have regular blood sampling and many patients were on a dose that was too high for them, given their age or renal function. Frail or elderly patients with a high bleeding risk need more frequent monitoring due to a risk of falls. Poor liver or kidney function may result in reduced excretion of the DOACs and thus increased drug concentration in the blood13 and risk of bleeding. Recently, experts have also recommended that NICE should include edoxaban in its guidelines for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in AF patients.1 Edoxaban is also 50% renally excreted. Serious deliberation regarding the effective implementation of current guidance and safety of patients on edoxaban may be required. To correctly follow the guidelines as set out in the CCG policy, it is important that vital tests are not omitted before commencement of therapy.

Testing in a reasonable time frame

Exploration of the policy shows that it fails to provide guidance on how to measure ‘frailty’ subjectively (e.g. self-management, care and support planning) or objectively using the eFI value of frailty severity (depending on disease states, signs and symptoms, disabilities and abnormal laboratory findings) or a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). Such ambiguity can prevent testing in a reasonable time frame and may further compromise patient safety. A critical review of Trust policies to include clear definitions may therefore be required. Similarly, the monthly interval for blood sampling is determined by dividing the patient’s eGFR value by 10. It is important to adhere to these calculated intervals to promote greater accuracy in management.

Importance of correct dosing

Of the risk factors that make up the CHA2DS2-VASc score, hypertension is associated with the greatest risk of stroke. AF patients with hypertension, even those whose only risk factor is hypertension could benefit from higher doses of anticoagulation to reduce the risk of stroke.14 An AF patient with a history of hypertension may be a complex patient and needs to be monitored by a specialist. Patients with hypertension could also have other contraindications for high drug doses (e.g. low eGFR), even though more aggressive thromboprophylaxis may be appropriate for them. Other CCGs may include a list of what is considered to be a typically ‘complex’ patient2 in updated versions of their policies. However, in cases where higher doses are contraindicated, lower doses must be administered to decrease the risk of bleeding.

Key Points

|

References

|

| Author Information

Dr Anisa Abdulrahman, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital |